A collection of meaningless meanderings. Perhaps you find them amusing, thought-provoking, or boring.

Strunk and White's Elements of (Life)Style

Strunk was trying to tell you how to live a good life.

Read moreIf you've studied English writing or grammar, you've probably come across the famous Strunk and White book. It's a short and to-the-point guide to writing style, and it's mostly built around 18 pithy statements that tell you how to structure your writing. It's an old book, probably around 100 years old now, but it's as useful today as it was in the early 20th century. I've read through it several times, starting in high school, and it's always great to come back to. It's cheap to buy a copy, but because the book is out of copyright, you can also find legal copies of the book for free online.

The more I read and thought about this book, the more I realized that these aren't just recommendations about writing; these are recommendations about living a fulfilling, minimalist, and positive life. There is an entire life philosophy that can be built around The Elements of Style. Well, OK, maybe not all of the style recommendations; some of the points really are just about English grammar. But many of the writing style points make great lifestyle points. Let me give you a few examples.

- "Use the active voice"

-

Grammatically, this means to construct sentences such that the subject is performing the action instead of the action being performed on the object. For example, instead of writing "Several tips will be presented," you should write "We will provide several tips." Another common example: Write "the dog chased the ball" instead of "the ball was chased by the dog."

As a life philosophy, I interpret this as a call to agency: be the author of your life and not a character in someone else's. Take ownership of and responsibility for your decisions, even the ones you regret. There are many instances in life where people feel that they are the passive recipient of an action instead of the agent of that action. Live your life, don't be lived by life.

But like all pieces of pithy advice, let's not take this too extreme: Few people enjoy the company of a control-freak, and you're unlikely to "win friends and influence people" by trying to be the sole author in every situation. This is, in my opinion, the wrong way to think about using the active voice in life.

Controlling situations or other people is trying to exert control over the outside world, the world outside your head. That world is notoriously difficult to control. There are geopolitical, economic, culture, and natural factors that you simply cannot control. From the weather to a virus to a foreign government starting a war, there are myriad forces in life that you simply cannot control; you really are the recipient of actions; the grammatical object of nature's verb.

But you do have more control over your inside world.

Let's also not take this too far: You cannot arbitrarily control all of your thoughts and feelings. You cannot eradicate ruminations, unhealthy thought patterns, depression, anxiety, intrusive thoughts, and other undesirable mental states by sheer force of will, any more than you can be rich by thinking that you are rich, or you can cure cancer by having a positive attitude.

I'll even take this a step further: Believing that you or someone else can dissolve their mental health issues simply by thinking positive is dangerous and insulting. It would mean that suffering from depression is a problem of not trying hard enough, when the truth is that depression is a biological disease that can take time, effort, and treatment to resolve.

Anyway, extreme cases aside, I maintain that use the active voice is one of the most profound and important of Strunk and White's tips for living a psychologically and emotionally satisfying life.

- "Put statements in positive form"

-

In terms of writing style, this point means you should avoid using the word not whenever possible. For example, instead of writing “I don't like loud bars” you could write “I prefer a quiet drink.”

In terms of a life philosophy, I interpret this to mean framing things in a positive light instead of focusing on the negatives.

That doesn't mean you ignore anything bad, it just means that you should try to be optimistic when you can. You know, every mistake is an opportunity to learn something. I recently heard a woman describe the death of her beloved young pet dog as "his final gift to me was the freedom to travel now that I don't need to stay home to care for him."

We all complain, and we all know people who complain. And we all know people who complain all the time and they are just tiring to be around. A little bit of justified bitching is find and cathartic; just try not to let cycle into a vortex of despair.

On the other hand, this pithy advice also shouldn't be taken too far. The world isn't all pink roses and unicorns. Shit happens, shitty things happen, shitty people do shitty things. Even good people do shitty things on occasion. Ignoring this fact of life, or desparately reframing everything to sound positive, is neither useful nor desirable. Even when it comes to grammar, Strunk is clear that the word "not" should not be banished from usage; rather, it should be avoided when possible.

- "Write in a way that comes naturally"

-

Grammatically, this statement encourages writers to use language that their readers can understand without extraneous effort. Prefer plain, simple, direct language over obtuse, complicated, verbose junk.

Is this also a life philosophy? Very few things in life "come naturally" when you first try them; instead, that feeling of ease comes from a lot of dilligent practice. I'm pretty happy with my own writing, and it feels "natural" to me, but that feeling took decades of hard work to develop. And I am not alone in this experience—many artists, performers, sports players, and really any other skilled professionals have worked hard for many years to feel and look "natural" in their profession.

As a lifestyle recommendation, I interpret "write in a way that comes naturally" as a suggestion to interact with people in a way that makes them feel comfortable. In other words, the advice is not about you feeling natural, it's about making the people you're with feel comfortable and at ease. Don't force them to expend extraneous effort to engage in discussions. That means picking a conversation topic and style that feels natural to them.

- "Do not overstate"

I get annoyed when conversations turn into a game of one-ups-manship.

What does that mean? It means that each person tries to convince the other that their experience (or that of someone they know) is more extreme. For example, person A tells a story about a near-accident while driving, then person B counters that their recent near-accident was worse, which leads person A to tell a story about their friend's car accident that was even worse, and so on. It's a game of who has the more extreme story to tell.

I tend to get caught up in them and participate in the escalating trading of stories. When I notice I'm engaging like this, I get annoyed at myself: Am I really so petty that I feel I have to "win" the game of one-ups-manship? When I notice this, then my reaction is to let the other person "win," finish that topic, and switch to something else. Usually I do it by telling a stupid joke, which is something I often do when I feel uncomfortable (though admittedly, I also tell stupid jokes when I feel comfortable, so the utterance of a stupid joke is not necessarily indicative of my internal mental/emotional state).

Anyway, I take Strunk's grammatical advice to advise people to be modest and factual, both in writing and in real-world interactions.

Here's a quote that I like, which seems a propos: A lie is sweet in the beginning and bitter in the end, while truth is bitter in the beginning and sweet in the end.

- "Omit needless words"

-

This is the most famous of Strunk and White's recommendations. As a continually aspiring minimalist ("maniacal minimalist" is probably more accurate), this one sticks with me the most.

In writing just as in real life, keeping things simple is harder than making things complicated. Writing, just like life, has a way of bloating and fattening beyond necessity. It takes skill, effort, and persistence to keep things simple.

Omit needless words means to cut out the unnecessary fluff from your life that you might think is actually embellishing, but is actually just distracting you from your main goals and the things that bring you contentment and satisfaction.

- N/A

-

Not all grammar points are easily applicable to life. For example, “do not join independent clauses by a comma.” Grammatically, this means that two separate ideas should go into two separate sentences; in other words, don't put things together that don't belong together.

While I agree with this advice for writing, I would disagree if interpreted as advice to avoid mixing different experiences in life. I mean, who doesn't like pomegranate seeds on pizza??

Other points are really not applicable to life without a herculean stretch of the imagination, e.g., "Form the possessive singular of nouns by adding 's". Let's not read into this book too much.

The grammar of life

Well, this musing isn't meant to be a treatise on life philosophy, so I'll leave it at this. Thanks for reading and I hope you enjoyed this musing. Definitely pick up a copy of Strunk and White's Elements of Style. It's a quick read and yet provides a lifetime of thought.

Hide text

This is not a post

Will pipes exist in 100 trillion years?

Read more- Magritte's pipe

-

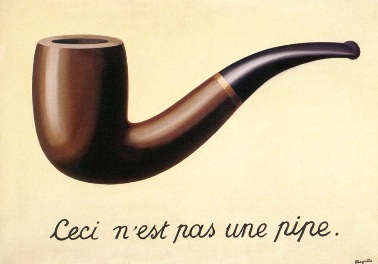

You might be familiar with this painting: It depicts a curved wooden smoking pipe, brown wood with a black mouthpiece, and shading indicating a light source on top and to the left of the pipe. Underneath the pipe is written "Ceci n'est pas une pipe"—This is not a pipe. It is called a "surrealist" painting, but on first glance it looks quite realist: The dimensions, size, lighting and shading, colors... it's not quite photo-realistic, but it's clearly a pipe.

So why does Magritte claim this is not a pipe?

Most people's first reaction (and mine as well) to this seeming contradiction is to challenge it: Of course it's a pipe! It's certainly not an elephant, a cement block, a hydrogen atom, a space alien, or any other of the uncountable number of things in the universe.

The retort to this reaction is that it is not literally a pipe. It is paint on a canvas (or, more likely nowadays, pixels on a screen), a two-dimensional depiction of a pipe. But it is not actually a pipe. You cannot put tobacco (or anything else) in it, light it, and smoke it. You cannot take it out of your smoking pouch in a cigar shop and pretend to be a sophisticated hipster when you actually look like someone desperate for attention. And you can do things with the digital version of that painting that you cannot do with a real pipe, like zoom in until it becomes pixelated, change the colors, and lots of other fun Photoshopy things.

- What is a pipe?

OK, so the picture is not literally a pipe; it depicts a pipe. It represents a pipe. Fair enough.

But what exactly is a pipe? Is there some prodigal pipe that exists somewhere in the Platonic plane, and all physical pipes are derivations of this pure pipe?

No, I don't think so. (I was tempted to write "obviously not," but I don't think it's obvious. We don't understand the nature of reality well enough to know with 100% certainty that there is no platonic realm that contains a pure pipe. But such a concept does seem unlikely, so I will proceed under the assumption that it is not the case.)

How many pipes have you seen in your life? I guess it's in the range of hundreds, possibly a few thousand. All of the pipes you've seen—and all the pipes you will see for the rest of your life (which I hope will be long and healthy and happy) share some features that make them "a pipe." You know, having a bowl to put the tobacco in, some tube-like extension, and a nozzle to put into your mouth to inhale the smoke. Individual pipes will have different shapes, weights, colors, patterns, and so on. But they all share some structural design features that allow them to be used for the purpose of burning something in order to inhale the smoke.

The point is that there are myriad instances of individual pipes, but each one is a pipe; there is no the pipe.

And this in turn means that the pipe is a concept. It exists in our brain as some pattern encoded in the physical structure of the brain, and when we see a physical thing, we can easily determine that it is a pipe.

- Where is The Pipe?

Here's the question I'm building towards: If all humans suddenly disappeared, would pipes still exist?

The millions of physical pipes that we have manufactured would, of course, continue to exist. Those are solid arrangements of matter that are still there when we put them into cupboards, the trashcan, or just look away from them. Sure, eventually they will cease to exist: Some day the sun will explode and vaporize the Earth and all the pipes with it. Perhaps before then, the pipes will break down or be digested by some bacteria that has evolved to convert man-made materials into their elementary compounds.

But are those physical things still "pipes" after we're gone? It's a question of where the concept of the pipe exists. If the concept exists only in our brains, then when our brains are gone, the concept no longer exists. Or has the concept of the pipe been somehow written into the universe because it had existed in our brains? The brain is a physical thing that exists, and so if a concept comes from a physical thing, then must it also be a physical thing?

Perhaps you might argue that the concept is a physical thing while we are alive, but it ceases to be a physical thing when we all die. But I'm not sure it's so simple. Stars are plentiful in the universe, but if the universe continues expanding, then there will be a time when stars no longer exist. (Don't worry, it won't happen in our lifetimes.) But at that time, stars will have existed, even if they don't exist at that moment. So maybe the concept of a pipe will—somehow—exist in 100 trillion years from now, even if there are no more brains to encode them.

- Back to the pipe

Does any of this matter? I don't think so. We can each live to be 1000 years old and live a happy, meaningful life without ever scratching the surface of Magritte's painting, beyond the direct interpretation that an artistic rendering is not the same thing as the actual physical object.

I'm not sure how deep Magritte intended us to go with his seemingly contradictory painting. But it made me think, and I suppose that is enough for art to be successful.

I have absolutely no idea if any of what I wrote above is true, nor am I arguing for a particular answer or perspective, nor do I hope to convince you of anything except that it's fun and rewarding to let your mind wander and record your thoughts. Indeed, I hope that you will disagree with at least some of what I wrote here, because that would mean that I've inspired you. And as much as I enjoy my own musings, knowing that I've catalyzed someone else's musings instills in me a feeling of meaning and purpose.

Do straight lines exist?

Do lines even exist outside our imaginations?

Toggle text- Little purple flying elephants

Do little purple flying elephants exist? Certainly not in our world. Probably not in any other physical world.

But certainly they exist in the world of the imagination. I can picture little purple flying elephants, with butterfly-like wings, faint pink spots that you'd see only on close inspection, and... I dunno, I think they like to wear green tutus on special occasions.

Do imaginary things exist? They come from our imagination, which comes from our brain. And our brain exists. Granted, we ("we" the scientific community) don't fully understand how the brain works, or how the imagination works. But certainly the imagination has some physical basis in the structure and dynamics of the brain, and among the myriad amazing things the brain can do is generate the concept of a little purple flying elephant that does not exist in physical form.

- Straight lines

-

Straight lines are, in my humble opinion, in the same category as little purple flying elephants. They exist in our imagination as an abstract geometric structure, but I don't think they really exist any more than our beloved loxodonta. Please allow me to explain.

Nature doesn't produce a lot of straight lines. Look around at the natural world: You won't find a lot of straight lines. Or any straight lines. (Footnote: "Natural" is an annoying word to define—for example, plastic bottles are made from chemicals that occur naturally—but I'm using the term "natural world" to refer to physical and biological objects that humans have not created using technology.)

The seemingly straight lines that humans have created are not, in fact, truly straight. The walls of a building are straight enough to provide structural integrity, but close inspection will reveal that they are "practically straight" but certainly not "truly straight."

What would it mean for a straight line to exist in nature? A straight line is defined as a line with zero curvature. No curvature at the galactic scale, no curvature at the scale of 100 km, no curves or bends at the scale of a millimeter, and so on. No matter how much you measure a straight line, or how closely you zoom into that line, it never curves.

I struggle with this definition. For one thing, space is curved by gravity, so would a straight line bend with the curvature of space, or would it stay straight through the curves, and thus actually appear to bend inversely proportional to the strength of gravity? A second problem arises as you zoom in to that line. Perhaps it is straight at the spatial scale of meters, millimeters, even picometers (a picometer is 10-12 meters). But keep zooming in and eventually we get to Planck scale (10-35 meters). At this scale, the concept of "length" is no longer meaningful because the uncertainties about where and when things happen are as large as the estimates themselves. I am not a physicist, but I think this means that cannot say for sure that a straight line continues to be straight at such tiny distances.

A brief tangent on Planck length

Planck length is around 10-35 meters, a typical human brain cell is around 10-3 meters, and the observable universe is around 1026 meters wide. Curiously, this means that a brain cell is roughly half-way between the tiniest thing in the universe and the biggest thing in the universe. The craziest part of this to me is that when we think about how incomprehensibly huge the entire universe is, that's how big a single brain cell would look to a "person" who is one Planck length tall. I cannot even imagine what a person that tiny would experience: Planck length is still a whopping 20 orders of magnitude smaller than a proton; even our lovely solar system is "only" 12 orders of magnitude bigger than a human.

Anyway, the point is that I cannot imagine that straight lines could exist at arbitrary spatial resolution. In my mind, that means that straight lines do not exist, not even imaginary ones.

- The Platonic Plane

So, straight lines do not exist in the real world, and they do not exist in my imagination. I suppose geometrists and Platonists would argue that straight lines exist as a Platonic Form—an abstract exemplar in a Platonic Plane, of which real-world objects are impoverished imitations. But this Platonic Form then either transcends our understanding of physics, or is someone else's imaginary reality that I do not share.

I think about this sort of question relatively often. I'm quite certain I have little idea of what I'm talking about and I am even more certain that I will never know the answer of whether straight lines exist (if there even is a single answer to that question). But I do enjoy letting my mind meander to these topics. Perhaps you agree with all, some, or none of what I wrote here, but I hope you found this musing thought-provoking.

Hide text

Is my fingernail part of me?

On the distinction between dead skins cells and the psychology of their treatment.

Toggle textI'm looking at my left thumbnail. I like my fingernails cut short with just a millimeter of white. When the nails get longer, I start rubbing them with my finger, which becomes increasingly distracting, bordering on obsessive, until I can get to my little nail clipper—or I pick at it until I gain some purchase and gently pull a piece of nail off.

Maybe that's not so pleasant to read, but I think I'm not the only one with these tendencies. There is something animalistic about targeting the fingernails for a spate of self-grooming that can border on self-destructive behavior. I notice that I'm more likely to attend to my nails when I'm stressed.

The left edge of the thumbnail, where it curves around to the skin, has a kink in it. An imperfection in the smoothness of the nail. I guess it's from my poor nail-clipping skills.

I am aware that my nails look respectable but imperfect. They tend to be a bit jagged. I do not use an emery board, nor do I clip my nails with the patience and meticulousness required to make them look "nice." It's not that I like my nails looking jagged—to be honest, I'd love to have perfect and beautiful nails that would make a watch-model jealous. I just can't bring myself to expend that level of effort.

Needless to say, that little piece of discarded nail that caused the barely noticeable concavity is not me. It's not a part of who I am. At least, I certainly hope it isn't, considering it is now irretrievably lost in a bathroom trash can in a villa in Bali—and I am writing this in an airport in Kuala Lumpur. On the other hand, that little bit of discarded nail contains my DNA, and might actually outlive me, though I doubt even the best space-alien tech could ever find it.

But how about the part of my fingernail that is left—is that part of me? I think not. It comprises dead cells that keep growing outwards, and I keep cutting them off. I certainly don't feel like a different person when I trim my nails.

But there is something about that kink in my fingernail that makes me feel like me. It is the fact that I notice the imperfection and have a mild desire for my nails to look picture-perfect although it is unlikely that I will ever make the effort or the expense to get a manicure. That's a trait that permeates many aspects of my physical appearance: I admit to a desire to dress like a dashing GQ model and yet I wear clothes that are respectable and look decent, but certainly nowhere near a classical gentleman-like showing. Even when I iron my button shirts, I do a quick-and-dirty job. I tend to keep my shirts for too long, so the edges of the collars have the color worn off.

But this "conflict" between my desire for excellence and my minimal effort to get barely half-way there does not extend to all aspects of my behavior. I'm much more perfectionistic about my writing, in particular, my textbooks.

So the imperfection in my nail is not part of me. But the fact that I used to bite my fingernails as a kid, then stopped and now use nail clippers but don't trim them to perfection although I am aware and mildly annoyed that they are imperfect—that feels like something that is part of me.

And what is that thing that is part of me? It is a behavioral characteristic, a tendency to think and react in a repeatable and predictable way. Is that characteristic localized somewhere in my brain, such that I could clip it out, creating a concave kink in the tissue that would eliminate my tendency to invest minimal-but-nonzero effort to look my absolute best? And would that missing part of me make me work harder to improve my outward appearance, or would it change my preferences so that I'm no longer interested in looking dapper?

Hide text

Can a scientist be an athiest?

On the difference between a scientist and a person.

Toggle textBefore you read the title of this musing, I'm sure your answer was Yes, a scientist can be an atheist—and may scientists are atheists. But then this musing would have been quite short (or really long; consider Richard Dawkin's The God Delusion).

I humbly offer a contrary opinion: A scientist can be, at best, an agnostic. (An agnostic is someone who does not firmly believe in the existence or non-existence of god, but instead believes that we cannot know the answer to whether gods or God exists.)

- On proving and disproving things

The fundamental problem with atheism is that it requires a firm belief that god does not exist. And the problem with that belief is that—as a scientist—it requires proof.

There are cases where it is possible to disprove hypotheses. For example, if I have an hypothesis that all humans have purple skin, then we would need to find only a single human being without purple skin to disprove my hypothesis.

But consider the hypothesis "no human can have purple skin" (excluding the occasional bruise). Disproving that hypothesis would require examining the skin of every human that ever existed, including in the past and in the future. That's not possible. So we cannot rigorously disprove that hypothesis; the best we can do is say that it's extremely unlikely based on available evidence. We can also decide that this isn't an interesting hypothesis and direct our limited resources and time on more important matters.

- Absence of evidence is not absence of evidence

This is a common phrase in science. It means that just because we do not have evidence for something, doesn't mean it isn't true. For example, is chewing on whale skin an effective treatment for depression? There is zero evidence that it is effective, but that's because no one's done the research; it's not because hundreds of scientists and millions of dollars have been exhausted to conduct multiple large-scale rigorous experiments that have convincingly shown that whale skin has no impact on depression. So we don't know whether it's an effective treatment (I'm pretty sure it isn't, but that's not the point here).

There are lots of things we believe without any evidence. Beliefs without evidence are often touted as something dangerous that only fools and troglodytes accept. To be sure, some beliefs without evidence are dangerous, like Qanon conspiracy theories. But there are myriad other beliefs that we all have that have no evidence and aren't dangerous. For example, I believe that if I smile when I randomly make eye contact with a stranger, it will increase their mood and that's one tiny positive contribution I can make to the world. I have absolutely no idea whether it's true. To be clear—this is an empirical question and it would be possible to conduct scientific research on the topic (maybe it's been done; I have no idea). But the point is that I have that belief and I have no idea whether it's true. I also believe that changing my work environment (e.g., different desks or cafes or coworking spaces or cities or countries) helps me think more creatively and flexibly. Again, I have absolutely zero real evidence for that belief; it's possible that it's true simply because I believe it. I also believe that if I use proper capitalization and grammar, my dear readers will take me more seriously. I believe that I sleep better if I don't use my bedroom for anything except sleeping (and perhaps a few other activities, but not working or paying bills).

- Unexplained vs. unexplainable

There is a big difference between knowing that something is not true, versus not knowing whether it is true. There is no compelling scientific evidence for god(s), but that doesn't mean that god does not exist. In fact, the history of science and religion is basically that science continues to provide non-magical explanations for phenomena that religions explain with magic.

Of course, not everything is currently explained by science, but that doesn't mean it's unexplainable. A thousand years ago there was no scientific explanation for lightning. If time machines existed, then any of our modern tech devices would be incredible god-like magic to people from the past.

- Agnostic scientists

Getting back to the main point: I do not think that a scientist can truly be an atheist, because atheism requires believing something for which there is absence of evidence. The best we can do is say that there is currently no rigorous, scientifically convincing evidence for god, and we therefore choose to dedicate our time and limited resources to solving more urgent or more deserving problems in science, engineering, and medicine.

- Personal vs scientific beliefs

I can take off my scientist hat and say that I do not personally believe that there is a god. I mean, maybe there is, but I doubt it. Perhaps there was some kind of higher intelligence that created physical laws and kicked things off at the Big Bang (but what created that intelligence?), but the idea of a "personal god" that listens to our prayers and helps us find our keys or lets our favorite sports team win seems really unlikely to me. For example, if someone steals my phone, a religious person might try to console me by saying that god made this happen so I'd learn a lesson about not relying on technology. Although I appreciate the motivation to make me feel better, this argument doesn't hold up to scrutiny: Why did god make someone else sin? Would they have to be punished? And how did god make them do it? Perhaps that person stole my phone because they were desperate for money, because of how they were born and the society they grew up in, how their parents raised them, how other people treated them, the forces of history that shaped society to a place where phones would exist and people would be poor and desperate to steal other people's phones... basically, the only logical conclusion is that god created the entire universe 14 billion years ago just so I could learn a lesson about protecting my phone (for the record, I've never had a phone stolen). It just doesn't make sense. Of course, I could be wrong—what is my understanding of the universe next to that of god (if such a thing exists)—but the idea that I am so important in the universe that god would make other people do bad things only so I could learn a little lesson is just so fantastically inconceivably egotistical and myopic.

And as others have mentioned (e.g., Stephen Fry), if such a personal god does exist and takes interest in us humans, then s/he is a selfish, belligerent, petulant asshole for causing so much senseless suffering and demanding such gratitude in return. And when something bad happens, we should excuse him because "god works in mysterious ways?" If a man rapes his wife, we don't forgive him because "men work in mysterious ways" and point out the times that he complimented his wife.

- Anyway...

OK, this musing meandered into raving territory towards the end. It's hard for me not to get frustrated by thinking about the achievements in society, art, human and ecological health, and technology that we could be enjoying now if people didn't successfully use religion as an excuse to justify their antisocial beliefs and actions.

I'd like to end with a return to my intellectual point: I don't know if such a thing like god exists. It's possible that god(s) exist, or that there are non-deity aliens that have such incredible technology that it will remain forever magical to us. But I am doubtful of both propositions (well, I'm not doubtful of technologically advanced aliens; I'm doubtful that we'll ever interact with them or them with us). There is no proof that god does not exist, neither is there compelling proof that god does exist (senseless arguments like "we don't understand X so therefore X is from god" are not compelling).

I wish I were an atheist. I envy atheists for their confidence. I believe that their voices of reason should overpower the religious nut-jobs who bring us closer to the demise of modern human civilization. But the best I can muster for myself as a scientist is agnosticism with a strong leaning towards nature being ruled by physical laws that can be explained and sometimes manipulated using the principles of science.

The cost of wine tasting

How much does it cost to bottle a moment?

Read moreWhen I lived in California, I tried to become a wine snob. I drank wine often, tried to focus on all those adjectives that people use to describe wine, and I went wine tasting whenever I could.

My favorite wine-tasting experience was this winery in the Santa Ynez valley in Southern California. It was a beautiful sunny day, perfect temperature, with friends... everything was amazing. Rather than the normal wine-tasting experience of standing at the bar and having wine poured in your glass as soon as you finish the previous, we got generous pours and were encouraged to go sit outside on the grass, smell the roses, and listen to the music that was playing from speakers hidden inside fake rocks.

Needless to say, it was a sensorily overwhelming experience, with beautiful sights, sounds, smells and tastes. Not to mention the beauty of alcohol-enhanced social philia.

There was one wine in particular that I really liked, and I decided to take home a bottle of it. The bottle was $80, and when I first saw the price, I thought "oh my god this is such a rip off!" How can this absolutely amazing wine be only $80? That's a steal, and the winery is basically giving it away. Mind you, I wasn't rich and this is certainly the most I've ever spent on a bottle of wine. But everything was so perfect that day, that $80 just felt like too little money for the quality of the experience.

I decided to save that bottle for some unknown future special occasion. I brought that bottle with me from California to Germany, and it sat in my room for a few years, patiently awaiting just the right moment. I guess that moment never presented itself, or maybe I just built up too much expectation for the moment ever to be right. There was one evening when I was with a good friend of mine. We were supposed to go to a party in Düsseldorf, but it was cold and raining and neither of us really felt like traveling. We were just sitting in my apartment having a comfortable silence and I thought "fuck it, let's just open up this bottle and enjoy the best wine I've ever had." With much excitement and story-telling, I openned the bottle and was overwhelmed... with disappointment. It wasn't a bad wine, it just tasted like a normal red wine. If you had told me that it cost two euros from the gas station, I would have believed you.

How did that bottle go from being so amazing that I thought $80 was 1% of its worth to being indistinguishable from a gas station Merlot? At first I thought maybe something happened to the wine: maybe the plane trip ruined it, maybe it wasn't meant to sit in a bottle for two years. But no, I don't think there was anything chemically wrong with the wine. I think there was something wrong with my brain.

Here's what I think happened: That experience of wine tasting, with the sights and the sounds and the smells and all of the positive emotions—that is what I wanted to bottle. To bottle that experience and open it up again at some point in the future... I would have paid $80,000 for that. (I didn't actually have that much money at the time, but I would have worked for it. It was worth it.)

But you cannot bottle a moment; you cannot preserve an experience in a piece of glass to open up on a cold rainy German evening. That moment happened, but it's gone, I can't get it back and I can't experience it again. The best I can do is try to make moments like that happen again in the future.

Hide text